Kate Duthu's Interview with Jeanette Willert

/POET INTERVIEW Jeanette Willert by Kathleen Duthu

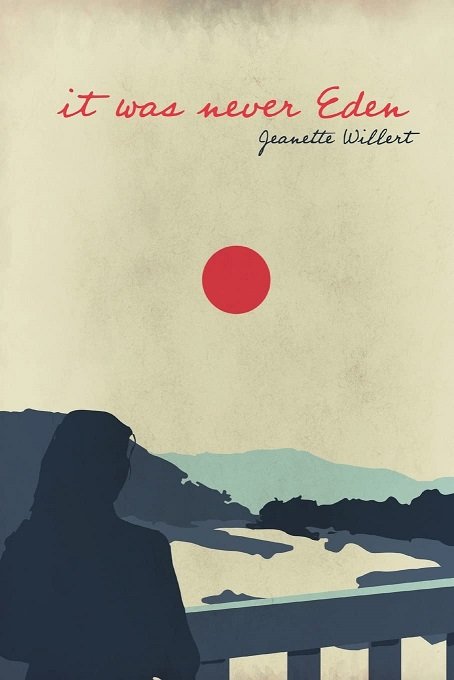

Born in West Virginia, the heart of Appalachia, Jeanette Willert writes frequently about her experiences growing up in a coal-mining family there. Her poems have appeared in numerous journals, magazines, and anthologies. She earned her Master of Arts and PhD in English Education from SUNY Buffalo. After more than three decades teaching high school students, she became an assistant professor at Canisius College in Buffalo, NY and served as the Director of the Western New York Writing Project before retiring as Chair of the Education Department. Fifteen years ago, she and her husband Richard moved to a log home on a lake near Birmingham, Alabama to be closer to her daughter and grandchildren. In retirement, Jeanette enjoys reading, writing, and participating in her poetry group and the Alabama State Poetry Society. Her chapbook, Appalachia Amour, won the 2017 Morris Memorial Chapbook Award. Negative Capability Press published her first full-length book of poetry, it was never Eden, in 2021 and it was awarded the 2021 Book of the Year by the Alabama State Poetry Society.

I spoke with Jeanette via Zoom while she sipped a morning cup of coffee at her desk, the sturdy wood beams and walls of her log home visible in the background. Both transplants to the deep South, we shared experiences of being out of our comfort zones and our unexpected love of small-town Waffle House restaurants. Jeanette appreciates the Waffle House servers at the Pell City, Alabama location regularly allowing her to occupy a booth to read and write long after they’ve cleared away her plate.

KD: As a former English teacher and college professor, who were your favorite poets and authors to introduce to your students?

JW: I taught English literature for about 35 years and American literature for a few years. I especially enjoyed teaching John Donne and Shakespeare and using lesser-known works to show different sides of the poets. Not surprisingly, students liked Donne’s poem, “The Flea,” because the speaker tries to persuade a woman to have sex with him. Shakespeare’s poem “Winter” would inspire students to write their own poems about winter scenes around their own homes, which were plentiful in New York. I also liked teaching about the Beat poets, particularly Lawrence Ferlinghetti and his poem, “Christ Climbed Down.”

KD: When did you start writing your own poetry? Why did you decide to publish your first your book at this point in your life?

JW: I first wrote romance novels while I was teaching then decided to go back to graduate school for my PhD in English Education in the 1980s after a publisher initially accepted then rejected one of my novels. When my husband and I moved to Alabama, I wanted to do something meaningful in retirement and found a local writers’ group. Most of the members were producing poems so I started with ten or twelve poems and now have about 250. The leader of the writers’ group encouraged me to submit to contests, magazines, and journals, which led to the collection for it was never Eden. I plan to publish more full-length poetry books.

KD: After reading your book, I can picture your coal-mining hometown of Kincaid, West Virginia, the Kanawha River, and the surrounding mountains. Do you still feel an intimate connection to West Virginia even though you haven’t lived there since you were a young newlywed?

JW: West Virginia will always be home, but things have changed since I grew up there. The only venue, other than a post office, left in my hometown is the Glen Ferris Inn where people associated with nearby chemical and metal plants stay. Hawks Nest State Park, a fabulous spot nearby, also brings some visitors. The newest national park is contiguous to the town where I grew up. I still have cousins living in that area and follow news and social media sites connected to the state. Outside interests run the state and aren’t interested in the welfare of the people, a very high number of whom live in poverty.

KD: Many of the poems seem autobiographical but explore universal themes including loss of childhood innocence, falling in love, and growing old. How do you want readers to relate to your poetry even if they’ve never been to any part of Appalachia?

JW: Geography is important, but human situations and experiences supersede place. Going to a funeral, attending a family reunion, or visiting a loved one in a nursing home are easily relatable. I’ve published several poems in an anthology of writers with ties to Appalachia, but the works reflect life, not just mountain life.

KD: You were not afraid to address some of the difficult parts of your family history, including racism by your relatives. What led you to write the poem “Beyond blood & bone,” which imagines how you would have a present-day conversation with your great-grandfather from Virginia who fought for the Confederacy and named his children after Confederate heroes? How and when did you learn about him in your family?

JW: I didn’t learn about my great-grandfather until I researched on Ancestry.com. My family focused on present day problems. My grandmother passed away when I was fourteen so I probably wouldn’t have been interested if she had talked about her father. As another poem describes, I found an old black and white photo of the Ku Klux Klan. My mother didn’t say anything about it, but I knew she shared her relatives’ racist attitudes. Fortunately, I escaped that prejudice. I attended a newly integrated high school in the 1950s and participated in a jazz band with both Black and White students. The band was led by a wonderful Black director who had played on the road with Count Basie. We all loved him.

KD: One of your poems, “Pandemic: March 26, 2020,” is very timely as we continue to face new variants of COVID-19. How has the pandemic impacted your writing? What were the challenges of releasing your book in 2021?

JW: I taught my students about the bubonic plague but never imagined we’d live through our own plague. I was very productive during the first year of the pandemic even though my writing group didn’t meet. I wrote the pandemic poem because I thought how strange it was to sit outside with friends watching nature spring to life around us, but we were socially distanced from one another because we knew the coronavirus could kill us. The pandemic, along with two hurricanes in south Alabama, delayed Negative Capability Press publishing the book until late 2021. I hope to have a few public readings and book events this year.

KD: As a transplant to the deep South, what do you enjoy about retirement living in central Alabama after working in Buffalo, New York for many years? I imagine you don’t miss shoveling snow during long winters.

JW: I like that spring now comes in February instead of May—it’s my favorite season. When I first retired, I tried painting for a few years but decided I’d need formal instruction to go further. Then I focused on writing but have avoided a rigid schedule like I had working as a teacher for so many years. Some days I write for several hours, but other days I don’t write at all. When my husband and I moved to Alabama, I hadn’t considered the challenges of being a New York liberal in a conservative area and still sometimes feel out of my comfort zone in the South.

KD: If you could be sitting anywhere in the world drinking a morning cup of coffee right now, where would it be and who would be with you?

JW: In Paris at a café on the Champs Élysées with a view of the Arc de Triomphe. I felt at home in Paris during my three visits but don’t think I’ll make it back there again. With me at the café I’d like Rumi, one of my favorite poets, and Shakespeare, whom I just love. I’d also like to talk with Jesus and ask him about how difficult it was to spread his messages of caring and loving people, especially during the days of the Roman Empire.

KD: Publishing your first book of poetry at the age of 80 is an inspiration for me. What advice do you have for “older” writers who have struggled to find the time, motivation, or confidence to create and put their work out into the world?

JW: The publishing world is not overly fond of older white women writers. Yet, when you are a writer, you write. . .regardless. I have been fortunate to “fall in” with a group of Alabama poets who are very encouraging. I have also had good luck in getting many of my poems in journals and anthologies. My advice? Write! Try local and regional sites for getting started publishing. Join a writing group. Join your state organizations for writers. Get out and meet those people!